**In the following update on a paper I am writing, I present numerous assumptions without providing adequate support or argumentation for any of them. In the complete paper, I will thoroughly defend all claims presented here; however, I opted not to do so at this moment, feeling that it would be excessive.**

In American Liberalism: How the 21st Century Convinced America Its Dream Was Earth’s Messiah, a paper I am in the preliminary stages of developing, I aim to explore how a nation, isolated from Halford Mackinder’s World Island (i.e., Eurasia where the bulk of the world’s resources and power is concentrated), became the world’s paramount leader, and how this ascent is intrinsically connected to the ideology that guides it.

“The American Dream is indefinitely more powerful than the narrow doctrines of Soviet communism. We must not delay much longer in putting it to work.”

Chester Bowles, New York Times 1951

In 2024 America, new publications seldom outright oppose the idea that liberty and equality should guide human affairs. This contrasts the 17th century’s Age of Enlightenment in Europe, when monarchies dominated and states openly pursued wars for power without the veneer of acting in the name of “humanity” (framing military interventions as part of a fight against human rights issues became common after the Nuremberg trials and the criminalization of “aggressive” warfare). During the Enlightenment, revolutionary ideas concerning the importance of human happiness and the pursuit of knowledge through reason were beginning to emerge. Notions such as natural law, liberty, progress, toleration, constitutional government, fraternity, and the separation of church and state were revolutionary.

As Russia and Chinas’ power resurges, coinciding with America’s decline and the rise of domestic populist movements in traditionally liberal nations, headlines forewarn the imminent demise of the liberal world order, conceived on Enlightenment ideals. Its conception of these ideals diverge from the original theories of Enlightenment philosophers, however, in part due to the widespread practice of liberalism that followed the American and French Revolutions. As such, today, these ideals are no longer primarily shaped by philosophers, but instead adjust as different governments apply them and they interact with diverse social social structures. Arguably the most significant influence on these evolving conceptions—despite the disdain some Europeans might express—is the US: the first modern democracy and the architect of the liberal world order.

To understand the emergence of the liberal world order, one must comprehend America’s ascendance in the international arena. This liberal world order remains an ideological order, founded on the principles of American Liberalism and what it says humanity desires, including open and free trade, liberal democratic governance, universal human rights, collective security, international institutions, and the rule of law.

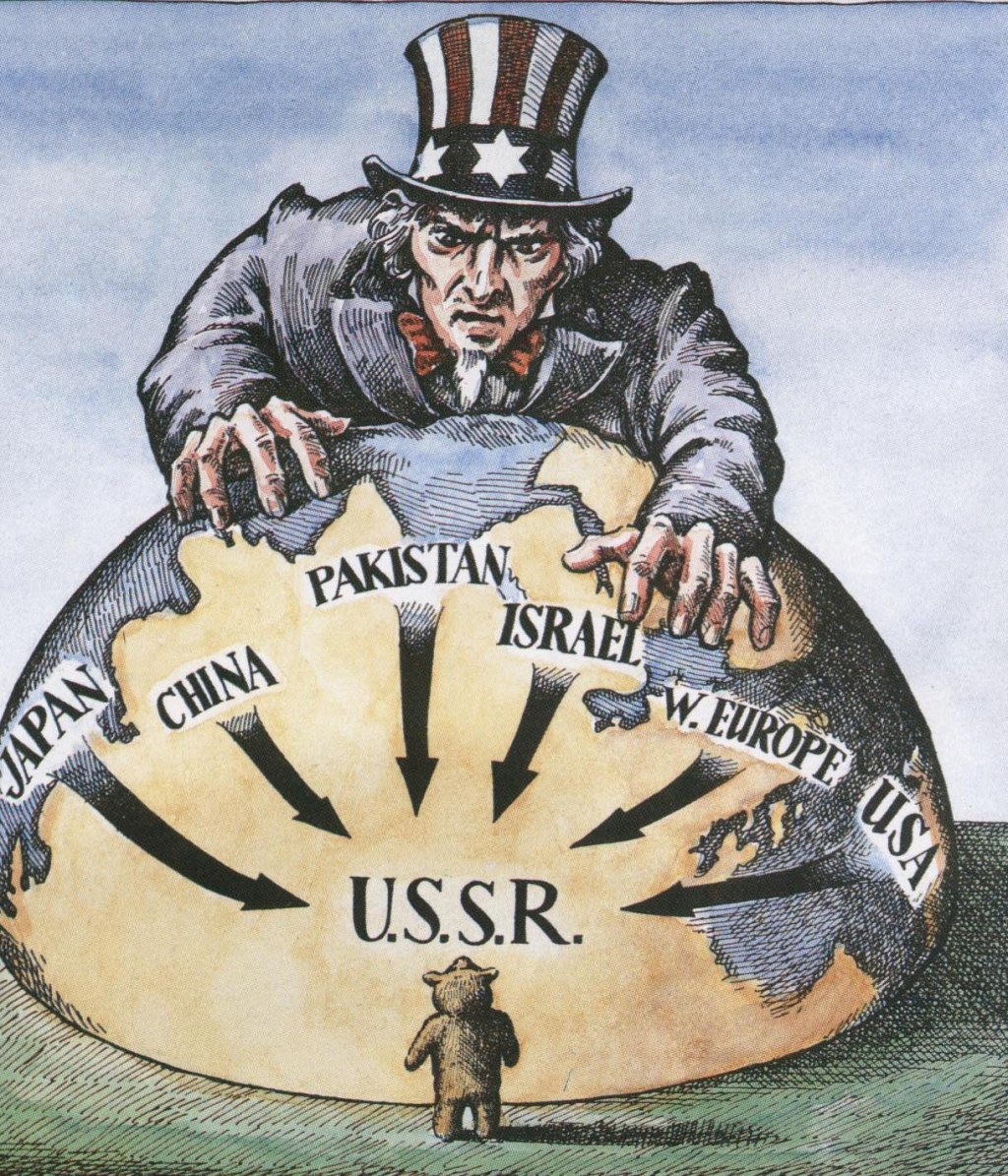

On May 13, 1951, the New York Time’s proudly declared “‘THE MOST POWERFUL IDEA IN THE WORLD’ our deep faith in the dignity of men is more than a match for the ideology of communism.” Within this article lies the sentence “a rearmed America confident of its strength, secure in its convictions, and dedicated to the democratic ideal of expanding human rights and opportunities for all people, can guide the free world.” The term ‘free world’ emerged as propaganda against a backdrop of early Cold War tensions, where the USSR and its Eastern European buffer states faced the liberal democracies the term references: the US and its beleaguered Western European allies. This term encapsulates the moral high ground the US felt over the Eastern Bloc: the belief that to be “free” states must conduct democratic elections and legislatively mandate equality and liberty (in the manner the US was conceiving them of course).

While no president has explicitly branded a distinct US ideology, a comprehensive analysis of US history clearly reveals a unique ideology that propelled a fledgling nation to global dominance: American Liberalism. Across the tenure of fourty-five presidents, American liberalism adapted and expanded many principles of enlightenment’s classical liberalism into a distinctive American dogma closely associated with the American Dream and American Exceptionalism, emphasizing individual rights, equality under the law, and government intervention to promote social justice and welfare.

When the 20th century’s world wars signaled the decline of European colonial dominance, it was American liberalism that convinced Americans of their unique capacity to fill the ensuing power vacuum, confident they knew the best path for humanity. At the core of American liberalism is a self-assurance that it represents the culmination of history, positing that because it protects and promotes rights it deems intrinsic to all humans, all people will eventually recognize its value. The universalism and progressivism inherent in this ideology drive the duty America espouses to disseminate these ideals worldwide and emancipate humanity, as echoed by the Times‘ assertion: “If our belief in human rights is something more than Fourth of July phrase or an election day promise, we have a clear responsibility to assist people across the seas to build a better and freer life.” While there is no immutable law that all of humanity desires liberty and equality, in America, there is.

“It belongs to us [Americans] to vindicate the honor of the human race, and to teach that assuming brother, moderation”

Alexander Hamilton, Federalist Papers

In my paper I will trace the development of American Liberalism, its past applications, and the future ramifications of its principles. I will employ it as a lens through which to explore the motivations of the US government in its foreign policy decisions. I intend to weave elements of history, philosophy, and even literary Schools of Criticism to provide a comprehensive analysis.

It will be structured into five sections:

1.) “We Hold These Truths To Be Self-Evident”: American Liberalism and its distinctive features

2.) “Well-Wisher to the Freedom and Independence of All”: the American Revolution to the Spanish-American War

3.) “In Search of Monsters to Destroy”: the dawn of the American Century to V-J Day

4.) “This Heresy of American Exceptionalism”: the USSR’s “worldwide” communist revolution to its dissolution

5.) “Unlimited Reserves of American Imperialism”: the American empire and ‘the end of history’

During the Cold War, as the US assumed an increasingly prominent role on the world stage, American interests complicated American values, with interests frequently taking precedence. In this paper, I am eager to explore the contradictions inherent in the ideals professed by American Liberalism and their application by the US government, which have contributed significantly to contemporary critiques of US foreign policy. One notable example lies in the US’ simultaneous criticism of its European allies’ colonization efforts while exporting American ideology to vulnerable nations. The US insisted that nations adopt governance structures reflecting American principles, framing it as a manifestation of humanity’s desires (recall the professed universalism of its ideology). Conversely, if nations chose alternatives, it was often attributed to them not knowing any better, thereby justifying American intervention to “liberate” them. The motivations behind ostensibly “righteous” Cold War actions like these, however, were often intertwined with fears of the spread of Marxism, propagated by the USSR, and the threat this may pose to US national security, reminding officials of the rise of the Axis powers. Exploring such complexities will aid in discerning whether the issues lie within American liberalism as a doctrine inherently, or in its application.

While American Liberalism granted the US unparalleled power in the 20th century, our failure to adapt it to evolving international circumstances is precipitating the decline of American power, rendering it no longer the endpoint of history. As contemporary politicians repeat the destructive decisions of their 20th-century counterparts, focusing on the short-term gains rather than long-term losses they eventually resulted in, public unease and political discord continue to escalate. The erosion of our global power will inevitably lead to a diminished quality of life, as we relinquish the privileges of being the world’s preeminent power.

“The brave new hopes of the one billion people of these underdeveloped areas can never be achieved without help. Their ability to strengthen their economies, establish stable governments, and offer expanding opportunities for the individual will depend on our willingness to provide bold and practical assistance. For the vast majority in the impoverished East, the primary consideration from day to day is simply survival, and we will find that people who are constantly faced with brutal facts of hunger and disease often view our concept of political democracy as a remote ideal…They are as suspicious as were then of foreign nations, which may result in a certain skepticism of our own good intentions, which will often try our patience…The stakes are no less than the future of the democratic ideal in America and throughout the world. If this ideal is to grow and expand, we must face up honestly to the weaknesses in our own democracy. We must offer vigorous assistance to other less fortunate peoples in the development of their economies. We must reject the isolationist concept of military power as an end in itself. If we fail, the ultimate hopes of the free world die with us.“

Charles Bowles, New York Times 1951

Leave a comment